Sumer (c. 3000–2000 BCE) – National Capability Assessment in its Bronze Age Context

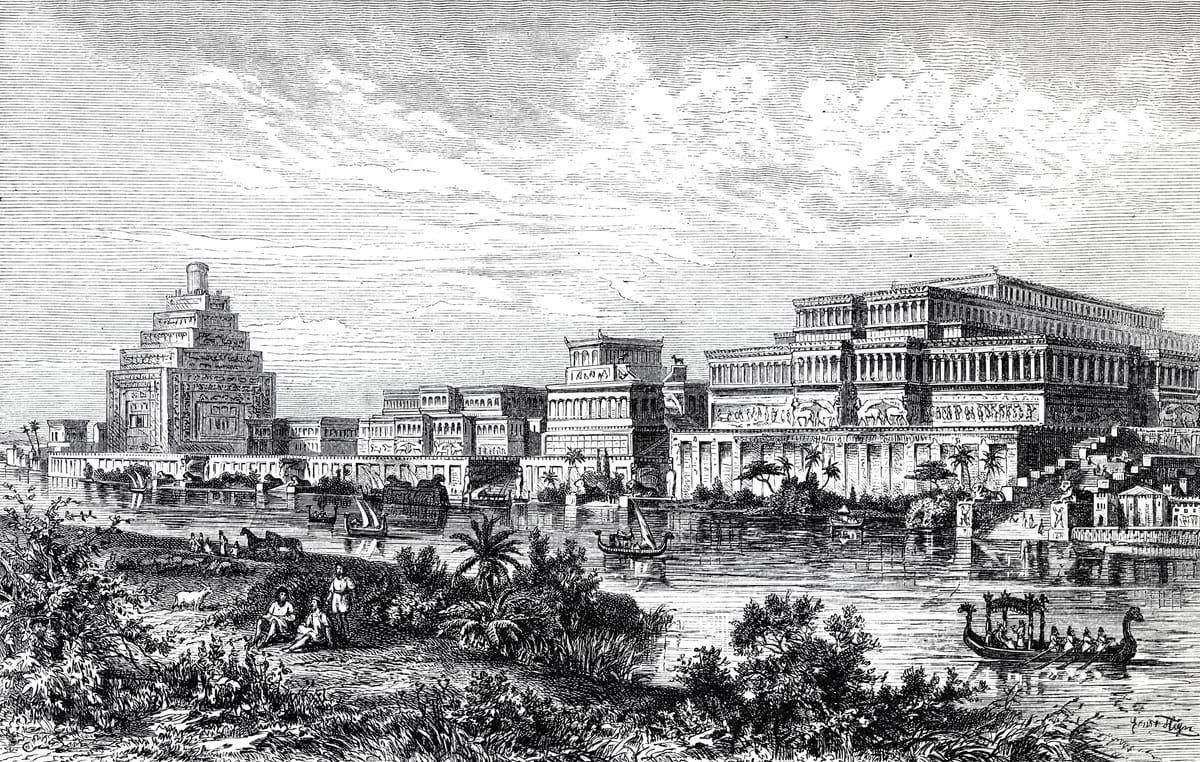

A cradle of urban civilisation, Sumer fused groundbreaking innovations, economic reach, and cultural influence to shape the foundations of statecraft in the ancient Near East.

Hard capabilities. Sumer led in foundational technologies (writing, wheel, sail) and fielded disciplined militaries shaped by frequent warfare. Its infrastructure was extensive (canals, levees, ziggurats) but built largely in mudbrick and required constant upkeep, leaving it less durable than Egypt’s stone architecture.

Soft capabilities. A sophisticated scribal tradition and cohesive cultural identity underpinned learning and internal legitimacy, though political fragmentation limited system-wide information control and societal cohesion compared with Egypt’s centralized model.

Economic capabilities. Sumer combined high irrigation agriculture, mass-production workshops, and far‑reaching trade and credit systems, placing it among the era’s most sophisticated economies; however, environmental salinisation and climate variability posed structural risks.

Sumer’s national capability profile reveals a civilisation that excelled in technological innovation, urban development, and economic sophistication, setting enduring precedents for statecraft in the ancient world. Its hard capabilities combined pioneering breakthroughs—such as writing, the wheel, and advanced metallurgy—with large-scale irrigation systems, monumental architecture, and a disciplined military shaped by a competitive geopolitical environment. These strengths enabled the transformation of the Tigris–Euphrates floodplain into a highly productive and densely urbanised landscape, supporting both daily subsistence and the grandeur of ziggurats and walled cities. However, the lack of lasting political unification limited the long-term strategic projection of these assets, keeping Sumer’s influence predominantly regional in scope.

Its soft and economic capabilities reinforced this foundation through a rich intellectual tradition, cohesive cultural identity, and one of the most advanced economies of the Bronze Age. Formal scribal education preserved and transmitted knowledge across generations, while temples and palaces acted as cultural and economic hubs that legitimised authority and coordinated trade. Sumer’s dual economic system—balancing temple-palace redistribution with vibrant market activity—leveraged agricultural surpluses, craft specialisation, and long-distance trade networks stretching to the Indus Valley and the Persian Gulf. Yet environmental pressures, particularly soil salinisation and dependence on stable trade routes, exposed vulnerabilities. Overall, Sumer’s blend of innovation, economic reach, and cultural influence secured its place as a foundational civilisation whose legacy shaped the political, technological, and cultural trajectory of the ancient Near East.

| Capability | Rating | Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Critical Technology | A− | Advanced engineering, writing, papyrus, metallurgy; lacked wheel but excelled in other innovations. |

| Strategic Infrastructure | A | Extensive irrigation, storage, and transport via Nile; enabled massive projects and stable food supply. |

| National Security | B | Strong defensive position, capable militia; focused on protection over expansion. |

| Human Capital | A− | Skilled scribes, artisans, and priests; healthy agrarian base supported productivity. |

| Information & Influence | B | Powerful internal cultural messaging; moderate regional influence abroad. |

| Governance & Integrity | A | Centralized divine kingship with effective bureaucracy; long-lasting stability. |

| Financial Strength | A | Command economy with large surpluses funding projects, trade, and famine reserves. |

| Production & Innovation | A | High output in agriculture, crafts, and mining; introduced efficiency-boosting technologies. |

| Investment & Trade | B+ | Strong regional trade network; focused on luxury and strategic imports, less global reach. |

Hard Capabilities

Hard Capabilities in Sumer reflected a civilisation operating at the forefront of technological and organisational advancement for its era. Its innovations in writing, transport, agriculture, and measurement created enduring foundations for statecraft and economic growth, while large-scale infrastructure projects transformed a challenging riverine environment into a productive and densely urbanised landscape. Frequent conflict—both internal and external—drove the development of disciplined military forces and fortified urban centres, ensuring survival in a competitive geopolitical arena. Together, these capabilities placed Sumer among the most capable and influential powers of the early Bronze Age, even if its lack of lasting political unity limited its strategic reach.

Critical Technology

Sumer pioneered a suite of transformative technologies that became civilisational baselines: cuneiform writing for administration and literature; the wheel (first as a potter’s wheel, then for transport); the sailboat for river and Gulf traffic; and the ox‑drawn plough that lifted agricultural productivity. Advances in metallurgy, standardised weights and measures, sexagesimal mathematics, and calendar-keeping entrenched a durable problem‑solving toolkit. These breakthroughs diffused widely across the Near East, placing Sumer at—or very near—the technological frontier of the third millennium BCE.

Strategic Infrastructure

Built on the Tigris–Euphrates alluvium, Sumer engineered dense networks of canals, levees, and dikes to manage volatile water regimes, store floodwaters, and irrigate fields. Its cities—Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Nippur—rose with monumental mudbrick architecture (ziggurats, walls, temple complexes) and canal‑side harbours that enabled commerce and labour mobilisation. While technically impressive and urbanising, this infrastructure demanded constant maintenance against silting, erosion, and flood damage, making it less enduring than Egypt’s stone-built projects.

National Security

Sumer’s geopolitical environment necessitated persistent readiness. Inter‑city rivalries and external threats fostered disciplined infantry (often depicted in phalanx formation), early war carts/chariots drawn by equids, fortified cities, and increasingly sophisticated bronze armaments. These capabilities enabled effective deterrence and episodic dominance within Mesopotamia. Yet the absence of lasting political unification constrained long‑range power projection compared with later territorial empires.

Soft Capabilities

Soft Capabilities in Sumer combined a highly developed intellectual tradition, rich cultural expression, and a governance framework rooted in both innovation and tradition. The spread of writing enabled formal education and specialised professions, sustaining a class of skilled scribes, artisans, and priests whose expertise underpinned state and temple operations. Religious and artistic production reinforced authority and transmitted shared myths across the Near East, while governance evolved through legal codification and administrative reform. Yet the absence of lasting political unity meant these strengths operated within a fragmented landscape, limiting the scope of coordinated cultural and institutional influence.

Human Capital

With writing came formal scribal schools (edubba) that trained administrators in cuneiform literacy, accounting, mathematics, and law. Large archives of tablets—administrative, legal, literary, medical, and lexical—attest to systematic knowledge transmission and professional specialisation among scribes, artisans, and priests. Agricultural surpluses supported significant non‑farming labour, reinforcing urban crafts and temple‑centered expertise across generations.

Information & Influence

Temples and palaces curated myth, liturgy, and visual culture (cylinder seals, stelae, monumental inscriptions) to legitimise authority and coordinate economic life. Sumer’s ideas—cosmogonies, flood narratives, divine kingship motifs—diffused across the Near East, especially during the Uruk expansion, shaping the cultural repertoire of successor states. While message control was effective within cities, the lack of a single sovereign centre limited empire‑wide narrative coherence.

Governance & Integrity

Sumer’s political order comprised autonomous city‑states ruled by lu‑gal or ensi, coordinating temple and palace economies through written administration. Despite fragmentation, Sumer developed legal codes, courts, and reformist traditions (e.g., debt relief, anti‑corruption edicts), and later experienced phases of re‑centralisation culminating in the Ur III bureaucracy. The result was a sophisticated but locally anchored governance system—strong in record‑keeping and institutional experimentation, yet vulnerable to elite rivalry and inter‑city conflict.

Economic Capabilities

Economic Capabilities in Sumer reflected a civilisation that combined agricultural surpluses, craft specialisation, and long-distance trade into one of the most sophisticated economic systems of the Bronze Age. Anchored by a dual structure of temple-palace redistribution and market-based exchange, Sumer integrated fiscal innovation with production efficiency and regional connectivity. Its ability to mobilise resources for both everyday needs and monumental projects was underpinned by irrigation-driven farming, large-scale workshops, and well-established trade routes that linked Mesopotamia to distant partners. While resilient in many respects, this economic system remained vulnerable to environmental pressures and the stability of its trade corridors.

Financial Strength

Sumer’s mixed redistributive (temple/palace) and market‑facing economy leveraged grain surpluses and silver‑based credit with standardised interest, contracts, and collateral. Standard weights and measures enabled reliable valuation, and state‑religious institutions could mobilise resources for large works and trade ventures. This fiscal-legal architecture was sophisticated for its time, though sensitive to harvest variability and the health of trade corridors.

Production & Innovation

Irrigated agriculture sustained large workforces beyond subsistence, enabling mass‑production workshops (notably textiles), organised metallurgy, ceramics, and woodworking at scale. Process innovations—standardised molds, batch production, logistical record‑keeping—raised throughput, while urban specialisation deepened craft quality. The ability to marshal labour and inputs across city networks underpinned both everyday consumption and monumental construction.

Investment & Trade

Resource scarcity pushed Sumer to invest in long‑distance exchange. Merchants and expeditions connected Mesopotamia to Dilmun (Bahrain), Magan (Oman), and Meluhha (Indus), importing copper, stone, timber, and luxury goods, and exporting textiles, grain, and crafted products. Canal‑harbour infrastructure, caravans, and written contracts underwrote these flows. The network was regionally extensive by Bronze Age standards, even if primarily oriented along Gulf and overland corridors rather than across multiple continents.