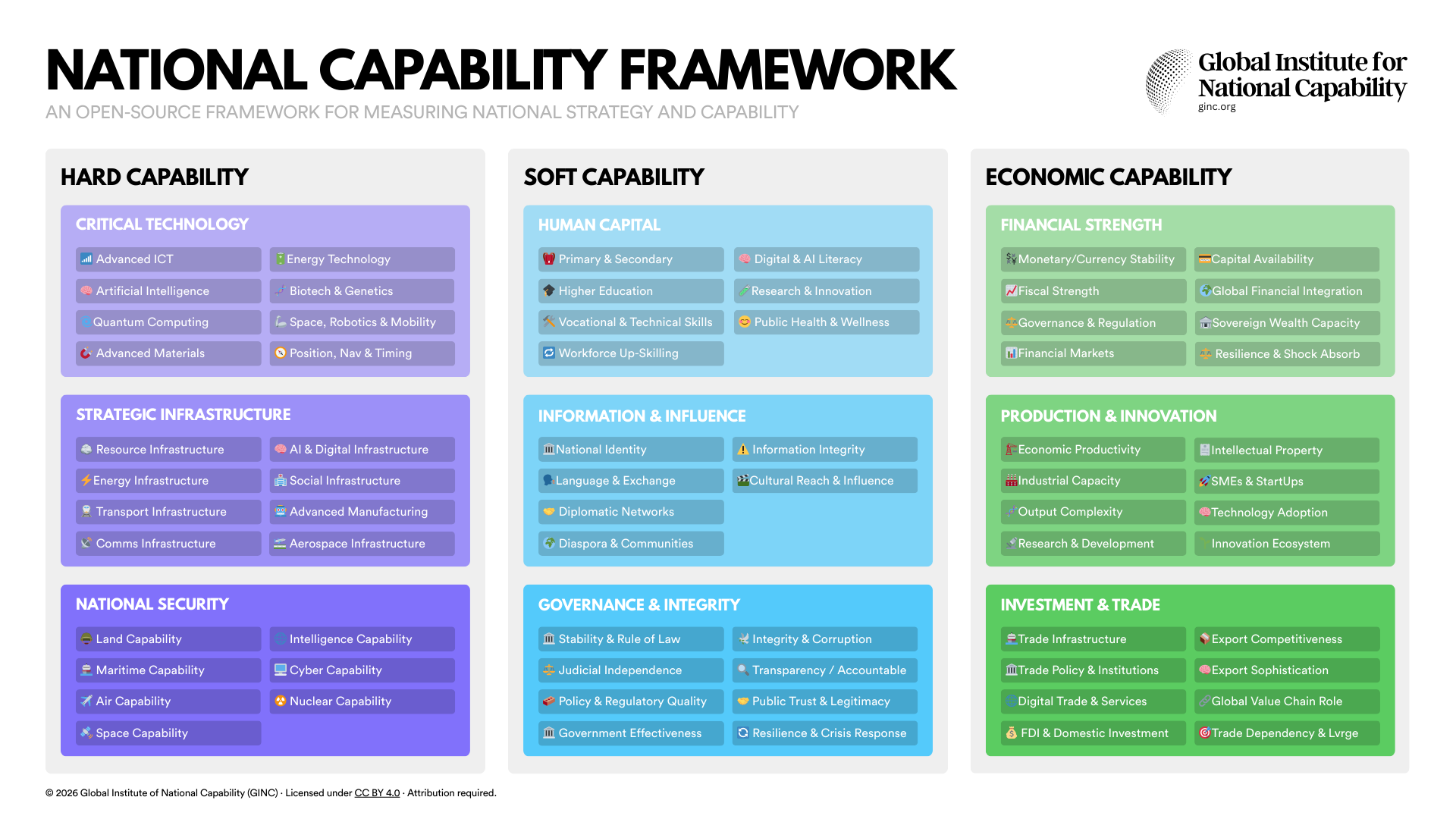

The National Capability Framework

The National Capability Framework maps the defining capabilities that shape a nation's power, prosperity and resilience, the generational systems, structures and frontier advantages that enable nations to endure, adapt and compound advantage over time.

In an era of rapid technological change and shifting geopolitical currents, understanding the true foundations of national strength has become more critical than ever. The National Capability Framework, developed by the Global Institute for National Capability (GINC), provides an analytical lens to systematically measure and benchmark a nation’s ability to pursue its strategic goals. Rather than focusing narrowly on military might or GDP alone, this open-source framework encompasses a broad set of tangible and intangible factors that collectively determine a country’s capacity for power, influence, and prosperity . By evaluating domains from human development to advanced technology, the framework enables policymakers, researchers, and analysts to identify critical gaps and strengths in national strategy. The emphasis is on capability – the underlying enablers of power – rather than power itself, reflecting GINC’s people-centered view that long-term resilience and competitiveness stem from robust national foundations .

Framework Overview

Framework Overview: The framework is organized into three domains – Hard, Soft, and Economic Capability – within which lie nine key dimensions (each dimension containing several specific components). The Hard domain covers physical and material pillars of power (such as resources, technology, and security forces). The Soft domain captures human, social, and institutional capital (ranging from education and health to governance and cultural influence). The Economic domain evaluates financial and productive strength and engagement in global trade. This structure recognizes that national strength is multidimensional: a country’s military or economic power cannot be viewed in isolation from its technological sophistication, human capital, governance quality, or integration in global markets . The following sections provide an analytical explanation of each dimension and its smallest components (e.g., Advanced ICT, Primary & Secondary Education, Trade Infrastructure, etc.), highlighting why each factor is vital to national capability. The discussion remains global and conceptual, avoiding specific country case studies or regional biases, to provide a neutral framework applicable to any nation.

| Power | Domain | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hard | Critical Technology | Capacity to design, produce, and secure critical dual-use tech like AI, semiconductors, quantum, and advanced materials. |

| Hard | Strategic Infrastructure | Core systems supporting mobilisation, deployment, digital networks, and resilient supply chains. |

| Hard | National Security | Ability to wage and deter conflict across land, sea, air, cyber, and space domains, including nuclear and hypersonic deterrents. |

| Soft | Human Capital | Education, health, skills, and global talent flows supporting productivity and cultural influence. |

| Soft | Information & Influence | Power to shape global narratives through media, culture, diplomacy, and digital platforms. |

| Soft | Governance & Integrity | Institutional legitimacy, leadership, rule of law, and ability to maintain domestic and international trust. |

| Economic | Financial Strength | Fiscal and monetary strength, currency credibility, and ability to absorb shocks and fund national goals. |

| Economic | Productivity & Innovation | Industrial capacity and innovation in strategic sectors with control of value chains and R&D outcomes. |

| Economic | Trade & Investment | Global economic connectivity through exports, FDI, agreements, and financial integration. |

Hard Capability

Critical Technology

Critical Technology refers to the advanced scientific and engineering capacities that drive a nation’s competitiveness and security in the modern era . In GINC’s framework it spans high-tech sectors such as information and communications, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, advanced materials, energy innovation, biotechnology, robotics, space technology, and position/navigation/timing systems. These cutting-edge technologies are considered “essential for a nation’s economic competitiveness, security, and technological sovereignty” . Nations that lead in critical tech can gain significant strategic advantages, fueling economic growth and enabling next-generation defense and industrial capabilities.

Figure 2. Critical Technology Capability Domain

| Upper Rating | Median | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 🇯🇵 AA | BBB | Transmitting information using light |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Wireless data transfer using radio waves |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | CCC | Underwater information transmission via sound waves |

| 🇨🇭 A | BB | Shared databases synchronised across multiple locations |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Supercomputers solving complex problems rapidly |

| 🇮🇱 AA | A | Decentralised networks without central infrastructure |

| 🇮🇱 AAA | AA | Protecting computers and data from threats |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Extracting insights from large data sets |

| 🇹🇼 AA | BBB | Designing and manufacturing microelectronic chips |

| 🇺🇸 A | BB | Making AI robust against malicious attacks |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Specialised hardware for AI computations |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AAA | Algorithms that improve through experience |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Computers understanding and generating human language |

| 🇺🇸 AA | A | Encryption secure against quantum computers |

| 🇨🇳 BBB | BB | Secure information transfer using quantum states |

| 🇺🇸 A | BBB | Computing using quantum mechanics principles |

| 🇩🇪 BB | CCC | Ultra-precise measurements using quantum effects |

| 🇩🇪 AA | A | Creating objects layer by layer |

| 🇯🇵 AAA | AA | Engineered materials combining multiple components |

| 🇺🇸 A | BBB | High-energy substances releasing power rapidly |

| 🇯🇵 BBB | BB | Materials conducting electricity without resistance |

| 🇮🇱 AA | A | Modern armour and protective materials |

| 🇩🇪 A | BBB | Protective coverings applied to surfaces |

| 🇳🇱 BB | B | Efficient chemical reactions in flowing streams |

| 🇨🇳 AAA | AA | Mining and refining essential raw materials |

| 🇩🇪 AA | A | Precision manufacturing to tight tolerances |

| 🇺🇸 A | BBB | Engineering matter at atomic scale |

| 🇬🇧 BBB | BB | Engineered materials with unnatural properties |

| 🇯🇵 BB | B | Materials responding dynamically to stimuli |

| 🇯🇵 AA | A | High-power, high-temperature semiconductor devices |

| 🇧🇷 A | BBB | Fuels produced from biological processes |

| 🇺🇸 BB | CCC | Focused laser or microwave beam systems |

| 🇨🇳 AAA | AA | Devices converting chemical to electrical energy |

| 🇺🇸 AA | A | Using electromagnetic spectrum for military advantage |

| 🇯🇵 A | BB | Low-carbon fuels for energy generation |

| 🇫🇷 AAA | AA | Power from atomic fission or fusion |

| 🇫🇷 BBB | BB | Safely handling radioactive materials |

| 🇨🇳 AAA | AA | Converting sunlight directly into electricity |

| 🇰🇷 A | BBB | Rapid energy storage and release devices |

| 🇺🇸 AA | A | Using living systems to produce materials |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Direct manipulation of organism DNA |

| 🇬🇧 AAA | AA | Reading and interpreting genetic code |

| 🇨🇭 AA | A | New drugs to combat resistant infections |

| 🇩🇪 A | BBB | Radioactive substances for diagnosis and treatment |

| 🇺🇸 AA | A | Designing and building new biological systems |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Biomedical preparations stimulating immune protection |

| 🇺🇸 A | BBB | High-speed propulsion beyond Mach 5 |

| 🇯🇵 AAA | AA | Autonomous robots performing complex tasks |

| 🇩🇪 BB | B | Submarine systems operating without atmospheric oxygen |

| 🇺🇸 AA | A | Machines performing tasks without human intervention |

| 🇳🇴 A | BBB | Self-navigating robots for ocean exploration |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Multiple unmanned systems working together autonomously |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | BB | Identifying objects travelling above Mach 5 |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Low-cost spacecraft under 500 kg |

| 🇺🇸 AA | A | Rockets sending payloads into space |

| 🇺🇸 AA | A | Ultra-precise timekeeping using atomic frequencies |

| 🇬🇧 BBB | BB | Measuring minute gravitational variations |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Self-contained position tracking without GPS |

| 🇩🇪 A | BBB | Detecting and measuring magnetic fields |

| 🇺🇸 AA | A | Capturing data across electromagnetic spectrum bands |

| 🇩🇪 A | BB | Detecting environmental changes using light |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | AA | Radio wave detection of object location |

| 🇺🇸 AA | A | Sound-based underwater detection and identification |

Strategic Infrastructure

Strategic Infrastructure covers the major physical infrastructures and industrial bases that support a nation’s economy and security. This goes beyond basic infrastructure to include systems critical for resource delivery, energy, transport, communications, manufacturing, and aerospace – essentially the backbone networks and facilities that enable a country to function and project power. GINC’s framework highlights that robust national infrastructure underpins resilience and prosperity, with components like resource and energy infrastructure ensuring self-sufficiency, and advanced manufacturing enabling industrial competitiveness. High-quality infrastructure reduces transaction costs and increases efficiency across the economy, directly contributing to economic output and connectivity . The components of this dimension reflect a comprehensive view of infrastructure: from traditional sectors (transport, energy grids) to modern needs (digital infrastructure and social infrastructure).

Figure 3. Strategic Infrastructure Capability Domain

| Upper Rating | Median | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 🇨🇭 BBB | D | Skilled labour and training systems |

| 🇨🇳 BBB | D | Raw materials and component supply |

| 🇨🇳 BBB | DD | Factories and assembly infrastructure |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Logistics and distribution networks |

| 🇺🇸 A | EEE | Aircraft and spacecraft production plants |

| 🇺🇸 AA | EEE | Research labs and test ranges |

| 🇺🇸 AA | FFF | Spaceport and servicing facilities |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | D | Software platforms and AI services |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | DD | Data centres and processing capacity |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | DDD | Datasets and information repositories |

| 🇰🇷 A | DDD | Fibre, 5G and backbone networks |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | DD | Hosting and cloud service hubs |

| 🇺🇸 AA | D | Orbital assets and frequency allocation |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | DD | Strategic reserves and storage facilities |

| 🇨🇳 BBB | DDD | Power plants and generation capacity |

| 🇨🇳 A | DDD | Grid networks and power delivery |

| 🇦🇺 BBB | DD | Mining and drilling operations |

| 🇨🇳 BBB | D | Refineries and material processing |

| 🇸🇬 A | DDD | Pipelines and bulk transport systems |

| 🇦🇪 BBB | DDD | Public amenities and cultural venues |

| 🇫🇮 AA | DDD | Schools, universities and training centres |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Hospitals and medical facilities |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Residential and welfare infrastructure |

| 🇸🇬 A | DDD | Airports and aviation systems |

| 🇸🇬 A | DDD | Roads, rail and transit hubs |

| 🇸🇬 AA | DD | Ports and shipping facilities |

National Security

National Security capability encompasses the defense and intelligence apparatus that protect a nation’s sovereignty and strategic interests. It spans traditional military domains – land, sea, air – as well as space, cyber, and intelligence capabilities. This dimension evaluates not the intent of using power, but the capacity to do so: the strength, modernization, and readiness of a nation’s armed forces and security services. A broad security capability ensures a nation can defend its territory, contribute to international stability, and deter aggression. GINC’s framework highlights intelligence and newer domains like cyber and space as equally critical alongside conventional forces . Each component here reflects a different facet of military power or security infrastructure that together form a comprehensive defense posture.

Figure 4. National Security Capability Domain

| Upper Rating | Median | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 🇺🇸 AAA | EEE | Fighter aircraft and air superiority |

| 🇺🇸 B | D | Transport and airlift capacity |

| 🇮🇱 BBB | EE | Rotary-wing close air support |

| 🇺🇸 AA | LP | Long-range precision attack capability |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | EEE | Intelligence gathering via networks |

| 🇮🇱 AA | DD | Network protection and resilience |

| 🇮🇱 AA | D | Disruptive and destructive cyber attacks |

| 🇺🇸 AA | DD | Geospatial and imagery intelligence |

| 🇮🇱 A | DD | Human intelligence gathering |

| 🇮🇱 A | DD | Measurement and signature intelligence |

| 🇮🇱 A | DDD | Open source intelligence analysis |

| 🇮🇱 AA | DD | Signals and communications intelligence |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | D | Tanks and armoured vehicles |

| 🇮🇱 A | D | Indirect fire and ground-based AD |

| 🇺🇸 A | EEE | Army helicopters and drones |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | DD | Ground combat troops |

| 🇺🇸 A | DD | Support, engineering and command systems |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | DD | Elite unconventional warfare units |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | EEE | Sea-based expeditionary forces |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | LP | Aircraft carriers and embarked air wings |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | EEE | Fleet logistics and replenishment |

| 🇺🇸 AAA | NP | Attack and ballistic missile submarines |

| 🇺🇸 A | EE | Destroyers, frigates and corvettes |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | NP | Command, control and safeguards |

| 🇺🇸 A | LP | Missiles, bombers and warhead systems |

| 🇫🇷 B | FF | Maintenance and modernisation programmes |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | FF | Assured access to space |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | EE | Orbital assets for comms, ISR and PNT |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | EE | Space situational awareness and denial |

Soft Capability

The Soft Capability domain encompasses the human, social, and institutional qualities that allow a nation to mobilize its people and influence others. Unlike hard assets, these factors are more intangible: the education and health of the populace, the effectiveness of governance, the power of national narrative and culture, and the extent of diplomatic and informational influence globally. Soft capabilities often translate into “smart power” – the ability to attract and co-opt rather than coerce. GINC defines this domain through dimensions of Human Development, National Leadership & Governance, and Global Influence (also referred to as Human Capital, Governance & Integrity, and Information & Influence in our expanded breakdown). These are the facets that determine how well a nation develops its human potential and leverages it on the world stage.

Human Capital

Human Capital refers to the strength of a nation’s education and skill base, health status, and capacity for innovation among its people . It captures how effectively a country cultivates its human resources – from basic literacy and numeracy to advanced scientific research – and how healthy and productive the population is. A nation’s human capital is a primary driver of its long-term economic growth and social development. This dimension comprises components spanning the educational ladder (primary to tertiary and vocational training), continuous workforce development, digital literacy, and the overall wellness of the populace. Together, these components indicate the quality of the labor force and the degree to which a country can create and utilize knowledge.

Figure 5. Human Capital Capability Domain

| Upper Rating | Median | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 🇮🇱 BBB | DDD | Specialist AI and ML skills |

| 🇪🇪 BBB | DD | Foundational digital literacy |

| 🇪🇪 AA | DDD | Internet connectivity and adoption |

| 🇨🇭 BBB | DDD | Graduate outcomes and job readiness |

| 🇸🇪 BB | DD | Tertiary education participation |

| 🇺🇸 A | DD | University research and citations |

| 🇫🇮 AA | DDD | School attendance and graduation |

| 🇩🇰 B | DDD | Inclusive education provision |

| 🇸🇬 AA | DDD | Student achievement and test scores |

| 🇪🇪 BBB | DDD | Healthcare availability and insurance |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Medical professionals per capita |

| 🇸🇪 BBB | DDD | Life expectancy and disease burden |

| 🇨🇭 AAA | EEE | R&D spending as share of GDP |

| 🇺🇸 AA | DD | Publications and patent filings |

| 🇨🇭 BBB | DD | PhD graduates and researchers |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DD | Work-based learning programmes |

| 🇨🇭 BBB | DDD | Accredited skills qualifications |

| 🇨🇭 AAA | DDD | Enrolment in vocational training |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DD | Continuing education engagement |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DD | Retraining programme availability |

| 🇨🇭 BB | DD | Corporate learning and development spend |

Information & Influence

Information & Influence covers the ways a nation projects itself and wields influence beyond brute force – through its culture, values, diplomacy, communication, and diaspora. It aligns with the concept of soft power, introduced by Joseph Nye, meaning the ability to get others to want what you want through attraction rather than coercion. The components in this dimension assess how a nation builds its identity and narrative, both internally and globally, and how it engages with international publics and partners. This includes cultural influence (movies, media, language), diplomatic networks, global communication strategies, diaspora relations, and the integrity of its information space. In essence, it’s about the credibility and appeal of a nation on the world stage and the coherence of its society at home.

Figure 6. Information and Influence Capability Domain

| Upper Rating | Median | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 🇺🇸 AAA | D | Film, music and media exports |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | DDD | Museums, libraries and archives |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | EEE | Hosting major international events |

| 🇺🇸 BB | DD | Remittances and overseas investment |

| 🇨🇳 BB | DD | Size and geographic spread abroad |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | DD | Diaspora soft power and lobbying |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | D | Shaping international priorities |

| 🇺🇸 BB | DD | Embassies and consulates worldwide |

| 🇺🇸 BB | DDD | Participation in international bodies |

| 🇪🇪 BBB | D | Countering foreign information operations |

| 🇺🇸 AA | DD | Global broadcast and digital media |

| 🇨🇳 BBB | DDD | State messaging and public diplomacy |

| 🇺🇸 A | D | Language speakers and learning uptake |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | DDD | Cultural and professional exchanges |

| 🇸🇪 BB | DD | International student mobility |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Inbound and outbound visitor flows |

| 🇫🇮 A | DDD | Public trust in institutions |

| 🇪🇪 A | DDD | Democratic engagement and volunteerism |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Social cohesion and crisis response |

Governance & Integrity

Governance & Integrity examines the quality of a nation’s domestic governance – the stability of its institutions, the rule of law, effectiveness and accountability of government, level of corruption, transparency, and ability to handle crises. Essentially, it’s about how well the country is managed and how much trust exists between the government and the governed. Strong governance ensures that resources (whether financial, human, or material) are utilized efficiently for public good, policies are implemented effectively, and citizens’ rights are protected. It also contributes heavily to a country’s attractiveness for investment and alliance, as nations with reliable governance are seen as safer partners. GINC frames this dimension around leadership and integrity , reflecting that national leadership quality and institutional integrity directly influence all other capabilities.

Figure 7. Governance and Integrity Capability Domain

| Upper Rating | Median | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 🇸🇬 A | DDD | Execution of government programmes |

| 🇪🇪 A | DDD | Civil service professionalism |

| 🇸🇬 AA | DDD | Public services quality and reach |

| 🇩🇰 A | DDD | Laws and enforcement mechanisms |

| 🇸🇬 A | DDD | Levels of public sector corruption |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DD | Standards of conduct and compliance |

| 🇳🇴 BBB | DDD | Legal aid and court accessibility |

| 🇫🇮 BBB | DDD | Fundamental freedoms and safeguards |

| 🇳🇴 BB | DD | Courts free from political influence |

| 🇸🇬 AA | DDD | Ease of doing business |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Clarity and coherence of laws |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Consistency and forward guidance |

| 🇪🇪 BBB | DD | Civic engagement and voting |

| 🇫🇮 BB | DDD | Equitable treatment under law |

| 🇪🇪 A | DDD | Public confidence in government |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DDD | Inter-agency emergency management |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Disaster planning and resources |

| 🇮🇱 BB | DDD | Post-crisis restoration capacity |

| 🇨🇳 BBB | DDD | Public safety and order |

| 🇨🇭 A | DDD | Government continuity and legitimacy |

| 🇩🇰 BBB | DDD | Consistent application of laws |

| 🇪🇪 A | DD | Open data and FOI frameworks |

| 🇫🇮 BB | DD | Press independence and pluralism |

| 🇸🇪 BB | DDD | Parliamentary and independent scrutiny |

Economic Capability

The Economic Capability domain centers on a nation’s financial and productive strength and its integration into the global economy . It encompasses the macroeconomic stability and resources a nation has (fiscal and financial strength), the efficiency and innovation of its industries (productivity and innovation), and the extent to which it engages and competes in international trade and investment. Essentially, this domain captures how well a country can generate and manage wealth – the fuel for both citizen welfare and the other capabilities (funding defense, education, tech development, etc.). As GINC notes, it involves Fiscal Capability, National Productivity, and Global Trade dimensions, reflecting that a truly capable economy must be stable and creditworthy, advanced in what it produces, and actively connected to the world.

Financial Strength

Financial Strength refers to the soundness of a nation’s fiscal and monetary foundations, the depth and stability of its financial system, and its capacity to mobilize capital for development. It’s about having the economic fundamentals in place: stable currency and prices, sustainable public finances, robust banks and capital markets, and integration into global finance (when advantageous). This dimension’s components cover monetary/currency stability, sovereign credit, growth trends, financial market development, international financial linkages, sovereign wealth, regulatory quality in finance, and capital availability. In combination, these indicate whether a nation’s economy is resilient to shocks, trusted by investors, and capable of financing both public and private sector needs.

Figure 8. Financial Strength Capability Domain

| Upper Rating | Median | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 🇪🇪 BBB | DD | Access to banking and financial services |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DD | Lending for projects and small business |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DDD | Corporate and consumer lending |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Adherence to Basel and FATF standards |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Banking supervision and regulation |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DDD | Autonomy of financial regulators |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Size and scale of banking industry |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | DD | Capital markets capitalisation |

| 🇩🇯 B | DD | Trading volumes and bid-ask spreads |

| 🇳🇴 BB | DDD | Government debt levels and trajectory |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DDD | Budget surplus or deficit position |

| 🇺🇸 BB | DDD | Credit ratings and borrowing costs |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DD | FDI and portfolio investment flows |

| 🇺🇸 A | DD | Role in IMF, World Bank and BIS |

| 🇺🇸 BB | EE | Currency use in global reserves |

| 🇨🇭 BB | DD | Autonomy of monetary authority |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DDD | Currency volatility and management |

| 🇸🇪 B | DDD | Price stability and targeting |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DDD | Capital adequacy and stress resilience |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DDD | Emergency liquidity and resolution |

| 🇳🇴 A | D | Reserves and stabilisation funds |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | D | Overseas asset holdings |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DD | Foreign exchange reserve holdings |

| 🇸🇬 A | EEE | State investment fund assets |

Production & Innovation

Production & Innovation looks at how effectively a nation turns inputs into outputs – essentially the efficiency (productivity) and sophistication of its economy. It examines the complexity of outputs (are you making simple goods or complex high-tech ones?), the productivity of labor, land, and capital, and the ecosystem for research and development, intellectual property creation, entrepreneurship, and technology adoption. This dimension is about the quality of economic activity, not just quantity. A country might have financial resources (from oil, for instance), but if it doesn’t excel in productivity and innovation, it may not be sustainable or competitive long-term. These components collectively indicate an economy’s internal dynamism and its capacity to upgrade itself.

Figure 9. Productivity and Innovation Capability Domain

| Upper Rating | Median | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Output per unit of input |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | DDD | Economic size and expansion rate |

| 🇸🇪 BBB | DDD | Efficiency gains beyond inputs |

| 🇸🇪 BBB | DD | High-tech production capability |

| 🇰🇷 B | EEE | Steel, chemicals and heavy industry |

| 🇨🇳 BBB | EEE | Refining critical minerals and metals |

| 🇮🇱 AA | DD | Emerging and cutting-edge tech |

| 🇨🇭 AA | DD | Innovation index rankings |

| 🇮🇱 BBB | DDD | Clusters and collaboration hubs |

| 🇺🇸 A | DD | High-value goods and services trade |

| 🇳🇱 BB | DDD | Tech diffusion and licensing |

| 🇰🇷 BB | DD | IP filings and registrations |

| 🇺🇸 BB | DD | Range of export products |

| 🇺🇸 A | DD | Complexity of production processes |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DD | Role in global supply chains |

| 🇮🇱 BBB | DD | Researchers and scientists |

| 🇮🇱 AA | DD | New products and processes |

| 🇮🇱 A | D | R&D spending as share of GDP |

| 🇮🇱 A | DD | New business formation rates |

| 🇮🇱 BBB | DD | VC funding and grants |

| 🇮🇱 BBB | DD | Business longevity and scale-up |

| 🇪🇪 AAA | DDD | Uptake of digital technologies |

| 🇸🇪 BB | DD | Spread of automation and robotics |

| 🇸🇪 BBB | DDD | Tech adoption across industries |

Investment & Trade

Investment & Trade covers a nation’s engagement with the global economy – how well it builds infrastructure for trade, attracts and directs foreign investment, competes in export markets, and manages its position in global supply chains and trade relationships. It assesses openness and connectivity: being open to trade and investment can drive growth, but also requires resilience to external shocks and ensuring dependency doesn’t become a strategic vulnerability. GINC’s framework highlights infrastructure, digital trade, FDI, export sophistication, and strategic trade leverage . The components here reflect how a country leverages global opportunities (trading goods, services, digital products, and capital) and how it guards or maximizes its interests in the global trade system.

Figure 10. Trade & Investment Capability Domain

| Upper Rating | Median | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 🇪🇪 A | DD | International data transfer capacity |

| 🇸🇪 BBB | DD | Online marketplaces and transactions |

| 🇺🇸 A | DD | Export of professional and tech services |

| 🇺🇸 B | DD | Pricing advantage in global markets |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DD | Spread of destination markets |

| 🇨🇳 BBB | DD | Volume and global trade share |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | EEE | Technology-intensive goods exports |

| 🇺🇸 A | DD | High-value goods and services |

| 🇨🇭 BBB | DD | Shift to higher-value products |

| 🇸🇬 BB | DD | Fixed investment and savings |

| 🇺🇸 BBB | DD | Cross-border direct investment |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Attractiveness to foreign investors |

| 🇸🇧 BBB | DD | Upstream or downstream role |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Links to major trade centres |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | D | Role in multinational supply chains |

| 🇸🇬 B | DD | Reliance on few products or markets |

| 🇺🇸 B | DD | Critical import vulnerabilities |

| 🇺🇸 BB | DDD | Economic coercion capacity |

| 🇸🇬 AA | DDD | Border clearance and handling |

| 🇸🇬 AA | DD | Maritime trade infrastructure |

| 🇸🇬 A | DDD | Air, sea and land linkages |

| 🇸🇬 BBB | DDD | Trade barriers and openness |

| 🇸🇬 A | DDD | FTAs and trade bloc participation |

| 🇸🇬 A | DD | Regulatory capacity and compliance |